BELGIUM:

One of the smaller states of western Europe. Under the Romans it formed one of the six provinces of ancient Gaul and bore the name "Gallia Belgica" (Gibbon, "Decline and Fall," vol. i. ch. i).

Early Settlement.There are no authentic records of the date of the earliest immigration of Jews to Belgium. According to a widely spread legend, their first settlement in this rich and fertile country occurred as early as the second century. Jewish merchants are said to have carried on at that time a considerable commercial intercourse between different parts of Asia Minor and the central countries of Europe. They followed the Roman legions in their path of conquest. In the wars of Vespasian and Titus a considerable number of Jewish captives found their way either willingly or unwillingly to Gaul and the Iberian peninsula. The defeat of Bar Kokba completed the dispersion of the Jews in the West; and the number of Jewish settlements in Gaul and Spain increased. In the fourth century their existence is historically attested. The original settlements were in the immediate vicinity of the Roman military posts, which formed a chain of communications extending all the way to Britain. Tongres and Tournai, in actual Belgian territory, are mentioned among the first places where Jews settled. They were also established in the chief seats of the provinces. At that period they appear to have enjoyed a considerable degree of freedom and prosperity. They were admitted to rights of citizenship; the tribunals treated them on a footing of equality with other citizens, and they shared and participated in the common duties and benefits of the state.

Under Frankish Rulers.The irruption of the Vandals did not affect, to any appreciable degree, the position of the Jews. They lived on in a state of complete tranquillity, undisturbed by adverse religious enactments and unhindered by commercial restrictions. The Frankish kingdom, founded by Clovis (486), included the whole of Belgium and embraced all the country beyond the Somme, and between the Meuse and the sea. The fortunes of the Belgian Jews were, therefore, for some centuries interwoven with those of their brethren in France. Like their sister communities, they were conditioned by the political and religious movements of the time. In general their state was exceedingly prosperous. They engaged in commerce, agriculture, and all forms of industry; and their argosies were seen in the rivers and on the seas. Nor was the profession of arms denied them; for they took a prominent part at the siege of Arles (508) in the war between Clovis and the general of Theodoric. Their conditionchanged but little till Chilperic (561-584), whose seat was at Soissons, conceived the idea of forcing his Jewish subjects to embrace Christianity. This zeal of a prince, whom Gregory of Tours designated as "the Nero of the Franks," met with little success. The Jews, despite these efforts, remained faithful to the religion of their fathers.

Under the early Carlovingians the Jews likewise enjoyed tranquillity. They were treated with humanity, and the favor accorded them by Pepin (751-768) attracted a vast number to his dominions. Their power and influence increased still more during the reigns of Charlemagne (768-814) and Louis le Debonnaire (814-840). Nor was their condition less prosperous under Charles the Bald (843-877). Between them and the Christians an almost perfect equality reigned.

The Feudal Régime.This period of wise toleration and protection ceased, however, with the rise of the feudal régime. On the dismemberment of the empire of the Franks, Belgium was partitioned into separate counties, duchies, and independent cities, in each of which a despotic sovereignty without regard to law or humanity prevailed. The Jews were handed over to the caprices of rulers who knew no other law but their passions. They were soon reduced to a deplorable condition. Restrictions without number were placed upon them, and they were robbed, despoiled, and massacred on every occasion and opportunity. The chronicles of the times abound with many tales of arbitrary and cruel deeds. Melart, in his history of Huy, relates how Ogier, count of Huy, on his return from the war waged by Otho the Great against Louis d'Outremer, found among his prisoners a rich Jew, upon whom he fastened an absurd charge of having secretly favored the invasion of the Normans. He was first tortured and then put to death, all his property being confiscated—a measure which was immediately followed by the expulsion of all the Jews from Liége and its province. It was always the wealth of these unfortunates that constituted their sole crime. With singular naïveté, Everard Kints ("Délices du Pays de Liége") observes that the justice and piety of this prince rose superior on this occasion to his political interests, for, as he afterward discovered, the whole commerce of the country, which had formerly been carried on by the Jews, received its death-blow on their expulsion. The clergy, too, who looked upon them as deicides, threw the weight of their influence against them. In 1160 Gauthier de Castillon, provost of the chapter of Tournai, wrote a diatribe in three books against the Jews, which excited the populace by its calumnies and imputations. It must, however, be said that not all the Belgian clergy were animated by a similar spirit of intolerance. On the contrary, many prelates were favorably inclined to the Jews, among others Wazon, bishop of Liége, who treated them kindly, and was on terms of great friendship with the Jewish physician of Henry III.

Prosperity Under Henry III.The epoch commencing with the thirteenth century was more favorable to the Jews of Belgium. They were subjected to less harsh and arbitrary treatment, and in the laws affecting them a spirit of fair discrimination appears to have been adopted. In a decree of Henry III. issued at Louvain, February, 1260, expelling the Jewish usurers, a distinction is drawn in favor of those engaged in honest trades, who were permitted to remain. This just distinction was not often made in those days; and more than once the whole of a Jewish population was held responsible for the crime of an individual. Under the shadow of this protection the Belgian Jews recovered somewhat their former prosperity. Commerce again flourished among them; and they engaged particularly in the study and practise of medicine. But the right to pursue these avocations had to be dearly purchased; and often the fruits of their industry became the prey of the exchequer.

After the death of Henry III. of Brabant (1261) his widow, Alix, upon whom the government devolved, finding herself in need of money, consulted the famous Dominican, Thomas Aquinas, on the question whether she could, without violation of conscience, draw upon her Jewish subjects for extra taxation, and, if need be, confiscate their goods. In itself this letter of the duchess is a proof that some sentiment of equity and humanity prevailed for the Jews of Brabant, and that they were under the shadow of some legal protection. The answer of Thomas Aquinas is a fine example of mingled casuistry and courtier-like subservience struggling against the better sentiment of religion. He argues that since much of the worldly possessions of the Jews represented the gains of usury, it would not be unlawful to deprive them of it: but he pleads that they should not be entirely despoiled; sufficient should be left to enable them to live. How the duchess acted in this matter is not known; but the Jews continued to reside and traffic in Brabant during the long and glorious reign of her son, John I. At that time flourishing Jewish communities existed not only at Brussels, but at Mechlin, Antwerp, Bruges, Ghent, Binche, Péronne, Ath, Tournai, Mons, Liége, Louvain, etc. A considerable accession to their numbers was made at the commencement of the fourteenth century, when Philippe le Bel expelled the Jews from France. William, count of Hainault, Vauthier of Enghien, and John II. of Brabant hospitably received them. The last-named prince accorded them special privileges and allowed them to establish banks for public credit. This charter was, however, revoked in 1307, Pope Clement V. absolving the prince from the oath which he took to grant this privilege in perpetuity. It is likely that the cancelation of the bank charter was due to a fresh influx of Jews in 1306, which must have disturbed the economic equilibrium, for the duke remained their stanch protector till his death.

Resettlement in Belgium.In 1321 the Jews were again expelled from France, and for a second time sought refuge within the borders of Belgium. The newcomers were allowed to settle in Mons, where a district was assigned to them for residence. They were permitted the free exercise of their religion and the right to pursue their avocations. Moreover, William refused to countenance an effort that was made to convert them.

Brussels Massacre of 1370.In 1337 William II. succeeded to the sovereignty of the state of Hainault. Following the example of his father, he confirmed the Jews in their privileges. These, however, had a considerable money value for the state. A document is extant (see below), dated Valenciennes, 1337, which grants to thirty Jews for five years a safe-conduct ("sauf-conduit") for a money charge of 2,000 florins. In the neighboring duchy of Brabant the Jews were no less fortunate under John III., who inherited all his father's goodwill for them. Unhappily, the Jews of Belgium at this time were, like their brethren all over Europe, persecuted on charges of having desecrated the host, of having killed infants, and of having poisoned wells. The storm that swept over the Jews of Belgium annihilated them; and so completely was the work of destruction done that scarcely a trace of their existence has remained. A series of massacres appears to have taken place during a period of twenty years, which finally culminated in the Brussels massacre of 1370. In the Metz Memorbuch, Brabant is mentioned as one of the lands in which Jews suffered in 1349 ("Monatsschrift," xiii. 36; Salfeld, "Martyrologium," pp. 270, 286). The particulars of these tragedies are involved in a good deal of obscurity. The following narrative in connection with the Black Plague is taken from Li Muisis, a contemporary historian ("Chronique Manuscrite de la Bibliothèque de Bourgogne," No. 13,076; see Carmoly, "Revue Orientale," 1841, p. 169):

Brabant Tax in 1370."In the city of Brussels, in the duchy of Brabant, where the duke had his seat, a large number of Jews resided, at the head of whom was a very rich man, said to be the treasurer of John III. The former was on very friendly terms with the duke. When the Flagellants arrived, carrying red crosses wherewith to inflame the people against the Jews, the treasurer hastened to the duke and entreated his protection. The latter assured him that no ill would befall them. But the people, already excited by the denunciations of the Flagellants, approached the duke's eldest son, demanding that they should be allowed to put all the Jews to death, and obtained from him a promise that he would intercede with his father, the duke, that no punishment should follow their action. They thereupon rushed with fierce cries to the Jewish quarter, destroyed the houses of the Jews, dragged their unfortunate victims through the streets, and without distinction of age or sex massacred them. Five hundred, it is said, perished on this occasion. Nor was the duke's treasurer spared. Taken alive and put to the torture, he was made to confess that he was engaged in the plots to poison the wells and to defile the consecrated host. He was burned alive. Similar butcheries occurred in other towns in the duchy, more particularly at Louvain, where the Jews were all delivered to the flames (1349 and 1350)."

Whether this narrative refers to a separate event, or is identical with the massacre of the Jews at Brussels on May 22, 1370, is open to doubt. The details of both are strangely similar. In each case the number of Jews that perished is given at 500. The principal Jew that figures in both narratives is the banker of the duke. The charges against the Jews are similar, and the mode of death is the same in both accounts. There can, however, be no doubt of the massacre at Brussels on May 22, 1370. The event has been locally signalized as the miracle of St. Gudule, and was commemorated by a periodical fête-day. Eighteen tableaux, representative of the various incidents of the piercing of the host and of the miracle of the blood spurting forth, were painted for the church, and are to this day an evidence of the blind fanaticism which wrought such dreadful havoc among innocent men, women, and children. But one solitary document in reference to this dreadful catastrophe has been unearthed in the treasury of Brabant. It is a receipt signed by Godefroi de la Tour, receiver-general of Brabant, who therein acknowledges the payment of the annual tax imposed on Jews living in Brabant. This is, in all probability, a page, or a fragment, of a collection of similar receipts. The following is a translation (see Carmoly, "Revue Orientale," 1841, p. 172):

"Received from the Jews who this year resided in Brabant, payment of their annual tribute and also of goods belonging to them received after they had been burned on Ascension Day, 1370. Accomplices in the crime of piercing the host: first, Wynand de Pondey, 14 francs; Arnold the Jew, 14 francs; Medey de Sallyn, 14 francs and 11 sheep; Medey Willacs, 22 francs; Simon Claere, 14 francs; Mestam, Joseph Wazoel, and Leonec, nothing, because they had left and were not residing this year at Brussels; the same of Wynandus the Physician, for he had not made payment of his tribute this year, although he resided at Brussels."

No other references to this massacre have come to light, either in the national archives or in the annals of local historians. "The neglect of the historians of that century," says Foppens, in his "History of the City of Brussels," "has been the cause why neither the edict nor the names of these sacrilegious Jews nor their sentences have been preserved."

On the Jewish side, the Memorbuch of Mayence commemorates the Jewish martyrs of Brabant. An elegy written in Hebrew in honor of the martyrs has been published by Carmoly, who has translated it into French ("Revue Orientale," 1841, p. 172). The Memorbuch of Pfersee, near Munich, recalls the martyred Jews of Flanders ( ), and so does Joseph ha-Kohen ("'Emeḳ ha-Baka," p. 55). "The Jews of

), and so does Joseph ha-Kohen ("'Emeḳ ha-Baka," p. 55). "The Jews of  ," says the latter, "were accused of profaning the host and adjudged to die. Many, however, saved themselves by conversion; and their descendants are still to be found numerously in that country."

," says the latter, "were accused of profaning the host and adjudged to die. Many, however, saved themselves by conversion; and their descendants are still to be found numerously in that country."

Few records have survived respecting the Jews who resided in the Middle Ages in the various states which comprised the Catholic portion of the Pays-Bas and of the Liége country, the greater part of which was formerly the territory of Belgium and of the grand duchy of Luxemburg. Nearly all that is known has been published by Baron de Reiffenberg, Carmoly, and Emile Ouverleaux. Koenen ("Geschiedenis der Joden in Nederland") has written of the middle countries of the Pays-Bas, and Felix Hachez of the Jews of Mons and of Hainault ("Essai sur la Résidence à Mons"), while Rahlenbeck has given an account of the Jews at Antwerp ("Les Juifs à Anvers," in "Revue de Belgique," 1871, pp. 137-146). But altogether there is a singular dearth of records both in Jewish and Belgian annals of the thousand-year-long stay of the Jews in Belgium. The materials for a full history of their social, intellectual, and religious condition are wanting. Benjamin of Tudela ("Itinerary," i. 106) has a passing reference to them, and the "Maharil" ( , 12a) speaks of the religious customsof the Jews of Flanders. They do not seem at any time to have attained, like their brethren in Spain and France, any importance in the world of learning and science, but appear to have been successful as physicians, bankers, and handicraftsmen. There is no mention of any scholars of note among them or of persons rising to positions of influence in the state except one or two financiers. Since, however, every vestige of written record has been swept away, it is impossible to say what their status really was.

, 12a) speaks of the religious customsof the Jews of Flanders. They do not seem at any time to have attained, like their brethren in Spain and France, any importance in the world of learning and science, but appear to have been successful as physicians, bankers, and handicraftsmen. There is no mention of any scholars of note among them or of persons rising to positions of influence in the state except one or two financiers. Since, however, every vestige of written record has been swept away, it is impossible to say what their status really was.

Yet, despite this almost total ignorance concerning the Belgian ghettos, many traces of their existence in every part of the country are still to be found. This is especially the case With the street nomenclature of nearly every Belgian town, which usually includes a "Jodenstraat" or "Rue des Juifs." Of those in ancient Brabant are the "Joden Trappen" or "Escaliers des Juifs," a group of five small streets situated near the hill De la Cour in Brussels; the "Jodenstraat" in Antwerp and in Louvain, and streets of like name in Cumptich, Tirlemont, Mons, Wasmes, Grosage, Bavai, Maroilles, Sains, Ghent, Looz, Spalbeek, Eupen, etc. In Tirlemont the Castel, formerly "Joden-Castel," was, without doubt, the ancient synagogue. A reminiscence of Jonathan, the banker, who was the head of the Brabant Jews at the time of the massacre in Brussels, is the Maison de Jonathas in the middle of Enghien. A vast plain situated outside the walls of that city also bears his name—Jardin de Jonathas. Many other localities and buildings with Jewish associations existed, the traces of which have nearly disappeared. Such are the "Jodenpoel," a fishery of the Jews of Brussels; the "Jodenborch" (synagogue) of Louvain, and the Château des Juifs in the Jodenstraat at Wommerson, near Tirlemont. Foulon, the historian of Liége, stateś that the Chirstrée of that town—i.e., Dog street—and a street of similar name in Huy derived their appellation from the former residence of Jews there, the name being evidently one of derision.

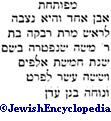

Scarcity of Records.The same fate of oblivion which has befallen their records has also attended the burial-places of the Jews of Belgium. The only memorial of that faroff past has come to light in the shape of a white stone with a Hebrew inscription found in 1872 in the grounds of a hospital at Tirlemont. Considering its age, the epitaph is well preserved; it reads as follows:

"This stone is inscribed and placed at the head of Mistress Rebekah, daughter of R. Moses, who passed away . . . in the year 5016 (1255-56). May she rest in the Garden of Eden!" The word  is evidently a misreading for

is evidently a misreading for  . The only other trace of a Jewish cemetery is mentioned by the Abbé d'Echternach, Jean Bertel, who, in speaking of the "Judenpforte" of Luxemburg, declares that, before the extension of the city on that side, the remains of a Jewish cemetery existed in its vicinity. Neither the archives of the various Belgian states and duchies nor the writings of local antiquaries and historians have yielded much toward any fuller elucidation of the history of the Jews of Belgium. The documents extant referring to them are exceedingly few. One, the safe-conduct edict, to which reference has already been made, is interesting for the names that it gives:

. The only other trace of a Jewish cemetery is mentioned by the Abbé d'Echternach, Jean Bertel, who, in speaking of the "Judenpforte" of Luxemburg, declares that, before the extension of the city on that side, the remains of a Jewish cemetery existed in its vicinity. Neither the archives of the various Belgian states and duchies nor the writings of local antiquaries and historians have yielded much toward any fuller elucidation of the history of the Jews of Belgium. The documents extant referring to them are exceedingly few. One, the safe-conduct edict, to which reference has already been made, is interesting for the names that it gives:

Elie de Maroel; Eliot, his valet; Douce; his cousin and son; Abraham-le-Mirre de Binche; Benoit, his son; Benoit, his son-in-law; Le Maistre des Juifs; Maistre Deie-le-Sire; Jacob Baron, Joie; Salomon de Doullers; Isaak de Péronne; Belevigne, his son-in-law; Maistre Sause; Jacob de Miekegnies; Michel de Pons; Amendanc, his uncle; Maistre Sause; Amendanc; Jacob de Foriest; Hagins de Péronne; Abraham de Nueville; Sause de Crespin; Maistre Lyon d'Ath; Abraham de Foriest; Hastée; Oursiel (brother of Lyon d'Ath); Floris de Mons (daughter of Maistre Elie).

The list includes a rabbi and five physicians; the rest were merchants and bankers.

The other documents comprise deeds and charters of the usual kind obtaining in the Middle Ages, and relate to the sale of property and to bonds for debts. M. Van Even (in "Louvain Monumental") cites a passage from a charter of the Abbey d'Averbode, dated 1311, wherein Rabbi Moses sells to Jean Van Rode, advocate, a house situated in the "Jews' street," near the cemetery of St. Peter of Louvain:

"Moyses Judeus, Judeorum presbyter, cum debita effestucatione tradit domum et curtem cum suis pertinentiis sitam in vico in quo Judei nunc commorantur juxta atrium S. Petri, Johanni de Rode Causidico."

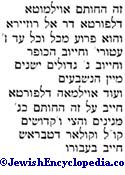

The only Hebrew document discovered in the royal archives is a memorandum on the margin of a bond contracted Oct. 26, 1344, to which Wilhemote delle Porte de Rosières Notre-Dame, debtor, and Master Sause, a Jew of Blaton, creditor, subscribe their names. The memorandum is a summary of the terms of the deed:

The archives of the Côte d'Or of Dijon contain two registers of Hebrew documents relating to transactions carried on by an association of Jews in France, Germany, and Belgium; and those of Luxemburg, notably of the castle of Clairvaux, have likewise many documents dealing with money transactions between Jews and the aristocracy.

Fifteenth and Following Centuries.It does not appear that any formal decree of banishment was issued against the Jews of Belgium; and it is very likely that after the massacre of 1370 there were fugitive Jews and their families whomanaged to settle again in the several communes. Not, however, till the middle of the fifteenth century do they reappear in Belgian history. One of their number, it is said, was chosen by the citizens of Luxemburg to treat with Philip le Bon in 1444 for the surrender of the castle. This would imply that there were some who even exercised an influence on public affairs. But their position was at all times of a precarious nature. They possessed no legal status, and under the houses of Burgundy and Hainault they were subjected to heavy and special taxation. The right of residence had to be dearly paid for. Every Jew who entered Luxemburg had to pay, if on horseback, a sum of 5 sols, and if on foot 2½ sols. Any one leaving the duchy was mulcted in 3½ sols. Besides all manner of other restrictions, the Jews in many parts were compelled to wear a distinctive dress. Under the pressure of these influences it is no wonder that the native Jews gradually disappeared from the Belgian provinces.

In 1477, by the marriage of Mary of Burgundy to the archduke Maximilian, son of Emperor Frederick IV., the Netherlands became united to Austria, and thereafter its possessions passed to the crown of Spain. The whole country, owing to the cruel persecutions of Philip II. of Spain and his attempt to establish the Inquisition, became involved in a series of desperate and heroic struggles. There is no doubt that the Jews played some important part in those stirring times. At the beginning of the sixteenth century a number of Maranos from Spain and Portugal began to arrive in the country. They were looked upon with suspicion, and Charles V., whom Cardinal Ximenes had prejudiced against them, refused them asylum, but they nevertheless managed to obtain a footing and to live there. They were rich and possessed of talent and enterprise, and evidently ingratiated themselves with the people, with whom they sided in their struggle against the hateful Spanish domination. Several attempts were made to expel them. In 1532 and 1549 and again in 1550 decrees were issued by the court against harboring Maranos, and citizens were bidden to inform the authorities of their presence; but this utterly failed of effect.

The duke of Alva, the Spanish governor, was especially severe in the repression of Jewish books. His edict of Feb. 15, 1570, ordered the expurgation of all errors from heretical books. On the advice of Arias Montanus and others, a list was prepared of such passages as ought to be expurgated, and a commission at Antwerp compiled an "Index Expurgatorius," the first of its kind (June 1, 1571). The Trent Index was published at Liége (Popper, "Censorship of Hebrew Books," p. 55). The number of secret Jews who entered the country increased daily. They, moreover, took an active part in the uprising of the Pays-Bas, the happy issue of which was to establish forever the principle of liberty of conscience in the United Provinces. The Jews labored assiduously in the cause of the people, and together with their brethren in Holland, who already enjoyed the right of publicly professing their faith, contributed materially to the success which crowned their efforts. They were strenuous supporters of the House of Orange, and in return were protected by it. But in that part of the Pays-Bas which remained under the dominion of Austria, the Jews, in contrast to their brethren in the Dutch Netherlands, were subjected to all the old restrictions and to hateful and discriminating enactments. In the treaty of peace (concluded April, 1609) between Albert of Austria and the States General it was stipulated that the subjects of either, excepting Jews, should be free to pass between the two countries. The intolerance of the archduke affected those only who publicly professed their faith, like the Jews of Amsterdam. In 1670, when the Comte Monterey succeeded the Duke de Feria, the Jews of Amsterdam petitioned for admission to the Pays-Bas. The count was at first disposed to grant the request; but clerical interference prevented its adoption.

There are few facts to relate concerning the Jews during the eighteenth century. They were still subjected to special imposts and harassing enactments; but, for the most part, that did not prevent them from growing in numbers and in prosperity. Many families of position and standing came from Germany and Holland and settled in the principal towns of Belgium. Among them were the Landaus, the Fürths, the Lipmans, the Hirshes, and the Simons, and to the last-named family belongs the chevalier Jean Henri Simon, a distinguished artist who had an adventurous career in the French Revolution. Under the influence of the Revolution, many Belgian writers and publicists took up the cause of the Jews. The most distinguished of these was the Prince de Ligne, who published a memoir defending them from the attacks of Voltaire, and eulogizing their virtues and character. He predicted for them a great destiny if admitted to full civil and political rights. A deep impression was made by this publication; and the Jews were soon placed on an equal footing with their fellow-citizens. In 1815 they obtained their full freedom. Thenceforward their political and social advancement and religious development proceeded on similar lines to those of their coreligionists in western Europe. For the history and condition of individual communities in the various towns of Belgium, see Antwerp, Brussels, Ghent.

The Jews of Belgium number about 12,000, and by imperial decree dated March 17, 1808, were divided into consistorial circumscriptions of nine departments, each comprising a synagogal district. The seat of the Central Consistory is at Brussels; and official communities exist at Antwerp, Arlon, Ghent, Liége, and Namur.

- Grätz, Gesch. der Juden, v. 43;

- Carmoly, Revue Orientale, i. 42 et seq.;

- Emile Ouverleau, Notes et Documents sur les Juifs de Belgique sous l'Ancien Régime, in Rev. Et. Juives, vii. 117 et seq., 252 et seq., viii. 206 et seq., ix. 264 et seq.;

- Monatsschrift, i. 499 et seq., 541 et seq., ii. 270 et seq.;

- Gross, Gallia Judaica, p. 124.