Preface

Owing to their long history and their wide dispersion, the Jews have been connected with most of the important movements in the history of the human race. The great monotheistic religions are based upon the Jewish Bible; medieval philosophy and science are inseparably associated with the Jews as intermediators; and in modern times there has been hardly a phase of human thought and activity in which the participation of Jews may not be discerned. While they have thus played a prominent part in the development of human thought and social progress throughout the centuries, there has been no faithful record of their multifarious activity. The Jewish Encyclopedia is intended to supply such a record, utilizing for this purpose all the resources of modern science and scholarship. It endeavors to give, in systematized, comprehensive, and yet succinct form, a full and accurate account of the history and literature, the social and intellectual life, of the Jewish people—of their ethical and religious views, their customs, rites, and traditions in all ages and in all lands. It also offers detailed biographical information concerning representatives of the Jewish race who have achieved distinction in any of the walks of life. It will accordingly cast light upon the successive phases of Judaism, furnish precise information concerning the activities of the Jews in all branches of human endeavor, register their influence upon the manifold development of human intelligence, and describe their mutual relations to surrounding creeds and peoples.

The need of such a work is sufficiently obvious. Jewish history is unique and therefore particularly liable to be misunderstood. The Jews are closely attached to their national traditions, and yet, in their dispersion, are cosmopolitan, both as to their conceptions of world-duty and their participation in the general advancement of mankind. To exhibit both sides of their character has been one of the objects of The Jewish Encyclopedia.

The history of the Jewish people has an absorbing interest for all who are concerned in the development of humanity. Connected in turn with the principal empires of antiquity, and clinging faithfully to their own ideals, the Jews developed a legal system which proved in course of time their bulwark of safety against the destruction, through external forces, of their national life. The Roman code, in its Christian development, assigned an exceptional position to the Jews; and it becomes one of the most interesting problems for the student of European constitutions to reconcile the status thus allotted to the Jew with the constitutional principles of the various Christian states. The struggle of the Jew to emancipate himself from this peculiar position has made him an efficient ally in the heroic endeavors of modern peoples toward the assertion of human rights.

Throughout all the divergences produced by different social environments and intellectual influences, the Jews have in every generation conserved the twofold character referred to above: as representatives of a nation, they have kept alive their Hebrew traditions; and, as cosmopolitans, they have taken part in the social and intellectual life of almost all cultured nations. In the period when Jewish and Hellenic thought came into mutual contact in Alexandria, they originated new currents of philosophie speculation. They then joined with the Arabs in the molding of the new faith, Islam, and of the entire Arabian-Spanish civilization. In the Europe of the Middle Ages, the process by which the science of Greece reached the schools of Bologna, Paris, and Oxford can be made clear only by taking account of the part played by Jewish translators and teachers. Scholastic philosophy was also influenced by such great medieval Jewish thinkers as Ibn Gabirol and Maimonides, while the epoch-making thought of Spinoza can be understood only by reference to his Jewish predecessors. In modern times the genius of the Jews has asserted its claim to intellectual leadership through men like Mendelssohn, Heine, Lassalle, and Disraeli. The twofold spirit of Judaism is displayed even through the medium of the Yiddish dialect, that modern representative of the Judæo-German of the Middle Ages. Preserved in this dialect, Jewish legends, customs, and superstitions, all of which still retain the traces of their connection with the various lands wherein the Jews have dwelt, serve to elucidate many an obscure feature of general folk-lore and ethnic superstition.

In the development of the Jewish faith and religious literature the same processes of internal growth and of modification through environment have incessantly gone on. The Bible, that perennial source of all great religious movements in western civilization, has been interpreted by the Jews from their own peculiar point of view; but their traditions on the whole represent the spirit of progress rather than the blind worship of the letter. The Biblical characters as they lived in Jewish traditions differed greatly from the presentation in the Scripture record. These traditions are embodied in the Rabbinical literature, with its corresponding Hellenic counterparts, those numerous Apocrypha which form the connecting links between the Old Testament and the New, between the Bible and the Talmud on the one hand and the patristic literature and the Koran on the other. Drawing upon these traditions, the Jews have gradually formulated their interpretation of the Law and an elaborate system of religious belief—in a word, Jewish theology. So, too, the Jewish system of ethics has numerous points of contact with the ethical and philosophical systems of all other peoples.

The Jews have been important factors in commerce through all the ages; the Egypt of the Ptolemies, the Rome of the emperors, the Babylonia of the Sassanid rulers, and the Europe of Charlemagne felt and acknowledged the gain to commerce wrought by their international connections and affiliations. In all the great marts of European commerce they were pioneers of trade until, with the rise of the great merchant-gilds, they were in some degree ousted from this sphere and confined to lower pursuits. It becomes thus a matter of supreme interest to follow the Jews through all their wanderings, to observe how their religious, social, and philanthropic activities were variously developed wherever they dwelt. To give a faithful record of all this abundant and strenuous activity is the proper purpose of a Jewish encyclopedia.

Hitherto the difficulties in the way of such an adequate and impartial presentation have been insuperable. Deep-rooted prejudices have prevented any sympathetic interest in Judaism on the part of Christian theologians, or in Christianity on the part of the rabbis. These theological antipathies have now abated, and both sides are better prepared to receive the truth. It is only within the last half-century, too, that any serious attempts have been made to render accessible the original sources of Jewish history scattered throughout the libraries of Europe. As regards Jewish literature, the works, produced in many ages and languages, exist in so many instances in manuscript-sources not yet investigated, in archives or in genizot, that Jewish scholars can hardly be said to command a full knowledge of their own literature. The investigation of the sociological conditions and the anthropology of the Jewish people is even now only in its initial stages. In all directions, the facts of Jewish theology, history, life, and literature remain in a large measure hidden from the world, even from Jews themselves. With the publication of The Jewish Encyclopedia a serious attempt is made for the first time to systematize and render generally accessible the knowledge thus far obtained.

That this has now become possible is due to a series of labors carried on throughout the whole of the nineteenth century and representing the efforts of three generations of Jewish scholars, mainly in Germany. An attempt was made, indeed, in the sixteenth century by Azariah dei Rossi toward a critical study of Jewish history and theology. But his work remained without influence until the first half of the nineteenth century, when Krochmal, Rapoport, and Zunz devoted their wide erudition and critical ingenuity to the investigation of the Jewish life and thought of the past. Their efforts were emulated by a number of scholars who have elucidated almost all sides of Jewish activity. The researches of I. M. Jost, H. Graetz, and M. Kayserling, and their followers, have laid a firm foundation for the main outlines of Jewish history, as the labors of Z. Frankel, A. Geiger, and J. Derenbourg paved the way for investigation into the various domains of Jewish literature. The painstaking labors of that Nestor of Jewish bibliography, Moritz Steinschneider—still happily with us—have made it possible to ascertain the full range of Jewish literary activity as recorded both in books and in manuscripts. The Jewish Encyclopedia now enters upon the field covered by the labors of these and other scholars, too numerous to mention, many of whom have lent their efforts toward its production and have been seconded by eminent coworkers from the ranks of Christian critics.

With the material now available it is possible to present a tolerably full account of Jews and Judaism. At the same time the world's interest in Jews is perhaps keener than ever before. Recent events, to which more direct reference need not be made, have aroused the world's curiosity as to the history and condition of a people which has been able to accomplish so much under such adverse conditions. The Jewish Encyclopedia aims to satisfy this curiosity. Among the Jews themselves there is an increasing interest in these subjects in the present critical period in their development. Old bonds of tradition are being broken, and the attention of the Jewish people is necessarily brought to bear upon their distinctive position in the modern world, which can be understood only in the light of historical research.

The subject-matter of this Encyclopedia naturally falls into three main divisions, which have been subdivided into departments, each under the control of an editor directly responsible for the accuracy and thoroughness of the articles embraced in his department. These are: (1) History, Biography, Sociology, and Folk-lore; (2) Literature, with its departments treating of Biblical, Hellenistic, Talmudical, Rabbinical, Medieval, and Neo-Hebraic Literatures, and including Jurisprudence, Philology, and Bibliography; (3) Theology and Philosophy.

1. HISTORY, BIOGRAPHY, AND SOCIOLOGY.

From the time of Josephus and the author of First Maccabees down to the nineteenth century Judaism did not produce a historian worthy of the name. What medieval times brought forth in this branch of literature were mostly crude chronicles, full of miraculous stories. Nor were the chronicles of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries much better.

But the interest displayed by Christian scholars of the seventeenth century in Rabbinical literature had the effect of directing attention to the history of the Jews. Jacques Basnage de Beauval, a French Protestant clergyman (1653-1723), has the merit of having done pioneer work with his "Histoire de la Religion des Juifs" (5 vols., Rotterdam, 1707-11).

The pioneer of modern Jewish history is Isaac Marcus Jost (1793-1860). His "Allgemeine Geschichte des Israelitischen Volkes," and "Neuere Geschichte der Israeliten," in spite of their shortcomings due to the lack of preparatory studies, were real historiographic achievements, while his "Geschichte des Judenthums und seiner Sekten" remains a standard work to the present day. Next to Jost is to be mentioned Selig (Paulus) Cassel (1821-92), whose article on Jewish history in the "Allgemeine Encyklopädie der Wissenschaften und Künste" of Ersch and Gruber (vol. xxvii.) may justly be called a memorable work. Both of these, however, were overshadowed by H. Graetz (1817-91), whose "Geschichte der Juden," in eleven volumes, although inadequate in many details, owing mainly to the absence of sufficient preparatory investigations, is still the only comprehensive and indispensable work on the subject. Since the appearance of Graetz's history, a great deal of critical research has been carried on by a number of younger scholars, the results of which have been published in monographs and magazines. The labors of Isidore Loeb, D. Kaufmann, and A. Harkavy in this field deserve special mention. The Jewish Encyclopedia, by stimulating research in detail, will have paved the way for the future writer of a universal Jewish history based on thoroughgoing scientific investigation.

The historical matter in this work is presented according to a system which may be indicated as follows: The history of all communities of any importance is given in detail; this information is summarized in connection with the various divisions of the different countries containing Jewish communities; lastly, a general sketch with cross-references to these subdivisions has been provided for each country. In addition to this, numerous general topics have been dealt with in their relations to the Jews, such as the Papacy, the Crusades, the Inquisition, Protestantism, etc. Strange as it may seem, there is no country that possesses an adequate history of its Jews, though of late years considerable activity has been shown in collecting material for such histories. There exists no comprehensive history of the Jews of Germany, Austria, France, Holland, England, Italy, Poland, or the United States, or even of such political divisions as Bohemia, Moravia, and Galicia, or of congregations of such historic importance as those of Amsterdam, Frankfort-on-the-Main, London, Prague, or Wilna.

Jews in America.

The entire field of the history, sociology, economics, and statistics of the Jews in America has hitherto been left almost uncultivated. There has, for example, been no attempt to present a comprehensive account concerning the foundation of the earliest Jewish communities, either in North or South America or in the West Indies. The developmental stages through which Judaism has passed in America, although of extreme interest, not only in themselves, but as promising to react upon the shaping of Judaism over all the world, have received but little attention. In The Jewish Encyclopedia the facts concerning Jews and Judaism in the New World are for the first time adequately presented.

Jews in Russia.

There is no section of Jewish history that has been more meagerly treated than that pertaining to the Jews of Russia. Graetz in his work devotes very little space to Russia, Poland, and Lithuania, a defect remedied to some extent in the Hebrew translation of his history, by S. P. Rabbinowitz, with notes by A. Harkavy. In the reform period of Emperor Alexander II. the government archives were partially thrown open, so that scholars like Harkavy, Orshanski, Fuenn, and Bershadski were enabled to furnish valuable material for the early history of the Russian Jews. Dubnow has contributed largely to the history of the Hasidim, the Frankists, and the old Jewish communities. In 1900 the first volume of the "Regesty i Nadpisi" (documents, epitaphs, and extracts from old writers) was published by the Society for the Promotion of Culture among the Jews of Russia; it covers the period from 70 to 1674. The 662 documents collected by Bershadski and published by the same society in 1882, under the title of "Russko-Yevreiski Archiv," contain material relating to the Jews in Lithuania from 1388 to 1569. Very little has been written about the development of the Russian Jews in the second half of the nineteenth century, although many of them have distinguished themselves in the industries and professions, finance, railroadbuilding, science, literature, and the fine arts. About 1,500 topics dealing with the Jews in Russia will be found included in The Jewish Encyclopedia, the greater part figuring for the first time in an English work, and the information being drawn in large measure from the most recent collections of Russian sources.

Of all branches of the science of Judaism, biography, and especially modern biography, has been most neglected. The whole Jewish biographical literature of the nineteenth century, general and individual, of any scientific value, would form only a very moderate collection. In the great biographical dictionaries of a general character, like those of Bayle, Moreri, Ladvocat, Michaud, and Hoefer, the "Allgemeine Deutsche Biographic," etc., Jews were almost entirely omitted. Only in the last two or three editions of such comprehensive encyclopedias as those of Meyer and of Brockhaus has Jewish biography received some attention, but the natural limitations of these books do not admit of detailed treatment. To a greater degree the want has been supplied by "La Grande Encyclopédie" and the "Dictionary of National Biography." But were one to take all national, local, and professional biographical dictionaries of the world together, one would find in them but a very small proportion of the Jewish biographies that appear in this Jewish Encyclopedia. There are biographical dictionaries of dead and of living divines and benefactors of the various Christian churches, but there is not a single systematically compiled collection of the biographies of the thousands of rabbis and Hebrew scholars, educators, and philanthropists who have worked prominently in the various countries of the world, and have contributed by their deeds to the spiritual and moral uplifting, as well as to the material welfare, of the Jewish people. The Jewish Encyclopedia is an endeavor to supply this deficiency.

While the present work has studiously sought to avoid exaggerating the merits of the more distinguished subjects of its biographical sketches, it has felt bound, on the other hand, to give due prominence to those less known men and women who have played an honorable part in Jewish life, and whose names should be redeemed from undeserved oblivion. The Jewish Encyclopedia will thus offer an alphabetically arranged register, as complete as possible, of all Jews and Jewesses who, however unequal their merits, have a claim to recognition. Under no circumstances, however, have personal or other motives been permitted to lower the standard of inclusion adopted for the Encyclopedia.

A word must be said touching two features pertaining particularly to the biographical department of a Jewish encyclopedia. It is often difficult in the case of writers, artists, and others, to determine positively whether they belong to the Jewish race, owing to the fact that social conditions may have impelled them to conceal their origin. To settle such delicate questions it has frequently been necessary to consult all manner of records, public and private, and even to ask for information from the persons themselves. While every care has been taken to insure accuracy in this regard, it is possible that, in a few instances persons have been included who have no claim to a place in a Jewish encyclopedia.

An even more delicate problem that presented itself at the very outset was the attitude to be observed by the Encyclopedia in regard to those Jews who, While born within the Jewish community, have, for one reason or another, abandoned it. As the present work deals with the Jews as a race, it was found impossible to exclude those who were of that race, whatever their religious affiliations may have been. It would be natural to look in a Jewish encyclopedia for such names as Heinrich Heine, Ludwig Börne, Theodor Benfey, Lord Beaconsfield, Emin Pasha: to mention only a few. Even those who have Jewish blood only on one side of their parentage—as Sir John Adolphus, Paul Heyse, and Georg Ebers—have been included.

In treating of those Jews whose activities have lain outside of distinctively Jewish spheres, it has been deemed sufficient to give short sketches of their lives with a simple indication of what their contributions have been to their particular fields of labor. Only occasionally, and for reasons of weight, has a departure been made from this policy. A summary of the contributions thus made to the various sciences will be found under the respective headings.

II. LITERATURE.

Bible.

How to deal with the vast amount of literary material that offered itself to the pages of a Jewish encyclopedia was a serious problem. While the Old Testament is the foundation of Jewish literature in all its aspects, as well as of Jewish life and thought, information on Biblical subjects is so readily accessible elsewhere that it did not seem desirable to develop the treatment of purely Biblical topics in these pages to the length which would be demanded in a work whose scope was confined to the Bible alone. In particular, it was considered unnecessary to compete with the "Dictionary of the Bible," prepared under the direction of Dr. Hastings, or with the "Encyclopædia Biblica" of Professor Cheyne, both published simultaneously with this Encyclopedia. While all sides of Biblical research are represented in these pages, they are treated concisely and, in many cases, with little reference to disputed points. With regard, however, to two special aspects of Biblical subjects, it has seemed desirable to treat the Scriptures on somewhat novel principles. Among Jews, as among Christians, there exists a wide diversity of opinion as to the character of the revelation of the Old Testament. There are those who hold to the literal inspiration, while others reject this view and are of the opinion that the circumstances under which the various texts were produced can be ascertained by what is known as the Higher Criticism. It seemed appropriate in the more important Biblical articles to distinguish sharply between these two points of view, and to give in separate paragraphs the actual data of the Masoretic text and the critical views regarding them. Again, there exists nowhere a full and adequate account of the various rabbinical developments of Bible exegesis—which would be of especial value to the Christian theologian and Bible exegete—and it was evidently desirable in a Jewish encyclopedia to devote considerable attention to this aspect of Biblical knowledge. The plan was adopted of treating the more important Biblical articles under the three heads of (a) Biblical Data, giving, without comment or separation of "sources," the statements of the text; (b) Rabbinical Literature, giving the interpretation placed upon Biblical facts by the Talmud, Midrash, and later Jewish literature; (c) Critical View, stating concisely the opinions held by the so-called Higher Criticism as to the sources and validity of the Biblical statements. As kindred to the rabbinical treatment of Bible traditions, it has been thought well to add occasionally (d) a statement of the phases under which they appear in the Koran and traditions of Islam generally.

It is here proper to point out that, inasmuch as the treatment of Biblical passages is mainly from the Jewish point of view, the chapter and verse divisions of the Hebrew text have, as a rule been adhered to in citations, while any discrepancies between them and those of the Authorized Version have been duly noted.

Hellenistic Literature.

In thus keeping abreast of the times in Biblical matters, The Jewish Encyclopedia aims to acquaint the student with the results of modern research in many fields that are altogether new and bristling with interesting discoveries. This feature of the work extends over the fields of Assyriology, Egyptology, and archeological investigation in Palestine, the inexhaustible treasures of which are constantly casting unexpected light on every branch of Biblical history and archeology. The soil of Africa has within the last thirty years enriched our knowledge of the life of the Jews of Egypt, and many apocryphal works unearthed there form a valuable link in connecting the Old Testament with the New, and the Biblical with the Rabbinical literature. The nineteenth century witnessed a great advance in the investigation of Hellenistic literature. The forms and syntactical constructions of the Hellenistic dialect have been set forth in dictionaries and grammars, so as greatly to facilitate the study of the documents. Valuable critical and exegetical works have shed light upon such topics as the texts of the Septuagint, of Aquila, and of Theodotion. Two new editions of Josephus have appeared, and the sources of his history have been investigated. The dates and origins of the apocryphal and pseudepigraphic books have been approximately determined. Around Philo of Alexandria a whole literature has grown up, and the true nature of his thought has been fairly well established. The result has been to determine with some definiteness the relation of the Hellenistic literature to the Jewish and Greek thought of the period, and its position in the general intellectual development of the age which produced Christianity. In these investigations Jewish scholars have taken a distinguished part. It has been the aim of The Jewish Encyclopedia to present in the most thorough manner the results achieved by critical investigation in the domain of Hellenistic literature. Of all Hellenistic productions of Jewish interest critical accounts and critical discussions are given; and the necessity of apprehending the ideas contained in them as products of their times, and of tracing their origin and development and their influence on contemporary and on later life, has constantly been kept in view. The New Testament, as representing the rise of a new religion, stands in a separate category of its own; yet from one point of view it may be regarded as a Hellenistic works—some of its authors having been Jews who wrote in Greek and more or less under the influence of Greek thought—and therefore its literature properly finds a place in the Encyclopedia.

Talmud.

The Talmud is a world of its own, awaiting the attention of the modern reader. In its encyclopedic compass it comprises all the variety of thought and opinion, of doctrine and science, accumulated by the Jewish people in the course of more than seven centuries, and formulated for the most part by their teachers. Full of the loftiest spiritual truth and of fantastic imagery, of close and learned legal disquisition and of extravagant exegesis, of earnest doctrine and of minute casuistry, of accurate knowledge and of popular conceptions, it invites the world of to-day to a closer acquaintance with its voluminous contents. The Jewish Encyclopedia has allotted to the subject of the Talmud an amount of space commensurate with its importance. Besides the rabbinical treatment of Biblical topics referred to, the Talmudic department includes those two great divisions known as the Halakah and the Haggadah, the one representing the development of the law, civil, criminal, and ceremonial; the other, the growth, progressive and reactionary, of the ethical principles of the Torah. The legal topics are treated from a strictly objective point of view, irrespective of their application, or even applicability, to our own days and conditions, but with incidental comparisons with Greek and Roman or with modern law, such as may be of interest to the student of comparative jurisprudence and of social economy. The Haggadah, on the other hand, attaining its fullest development in its treatment of the Biblical text, is therefore frequently included in the second paragraph of the Biblical articles. While in other directions its utterances bear more directly upon matters of theology, much remains both in legend and in proverbial wisdom which is discussed under the appropriate heads.

The rabbis of Talmudic times—the Tannaim and Amoraim—those innumerable transmitters of tradition and creators of new laws, receive ample treatment in the pages of the Encyclopedia. Not a few of them mark epochs in the development and growth of the halakic material, while others are interesting from their personal history or from the representative pictures of their times which their lives and teachings afford. Most of them being at the same time teachers and preachers, their biographies would be incomplete without specimens of their homiletic and ethical utterances. Those familiar with the labyrinthine structure of the Talmudim and Midrashim as far as arrangement of subjects and chronological order are concerned, and with the chaotic state of the text, particularly with regard to proper names, need not be told that the difficulties in identifying men and times are sometimes insurmountable, and much must be left to conjecture, in spite of the efforts made both in early ages and in recent days. The composition not only of well-known haggadic and halakic collections, but also of the single treatises of the Mishnah, will be separately treated. The work of Zunz, Buber, and Epstein in the province of Haggadah, and that of Frankel, Brüll, and Weiss in Halakah, have rendered it possible to give a history of Talmudic literature.

Rabbinical Literature.

What the Bible had been for the Talmud, the Talmud itself became for the later Rabbinical literature, which, based on the Talmud, applied itself to the further development of the Halakah and the Haggadah. Although this Rabbinical literature extends over a period of 1,400 years, and represents the only genuinely Jewish writings of that period, it is the least understood, not to say the most misunderstood, department of Jewish literature. The present Encyclopedia affords for the first time a survey of the growth of the Halakah and the Haggadah in post-Talmudic times (500-1900). During that period, the civil and religious laws of the Jews, although based upon the Talmud, underwent many a change, while the Haggadah developed new motives and broadened its foundations, until it differed essentially in character from the Haggadah of the Talmudic times. Two new branches were developed: the dispersion of the Jews in this period throughout the civilized world produced the responsa literature; and the exclusion of the German-Polish Jews from all share in general culture produced casuistry. A subject that has received due consideration is the period of the Geonim (500-1000), which, though not spiritually productive, powerfully influenced rabbinical Judaism.

An attempt has been made to fill the hitherto existing gap in literary history in regard to the activity of the Arabic-Spanish school (1000-1500) in the labyrinth of the Talmud, and equal consideration has been bestowed upon the French, German, and Italian Talmudists of the same period, to whom is largely due our knowledge of the Talmud, and through whose initiative the Jewish spirit was diverted to new lines of activity and kept alive when it was denied every other mode of asserting itself. Adequate attention has been given to the Rabbinical literature of the past four centuries, which have been chiefly characterized by the casuistic works of the German and Polish Talmudists, and the critical treatment of the Talmud in recent times finds full expression in these pages.

Jews have written in almost all languages that have a literature, and the Encyclopedia has taken account of this literary activity in its broadest range. The vast majority of productions of Jewish interest are, however, written in Hebrew and the allied tongues, and greater attention has naturally been paid to this section of Jewish literature. While the Encyclopedia does not attempt to give a complete bibliography of this extensive subject, it is hoped that there will be found under the various authors' names an account of almost all works of importance written in Hebrew.

History of Literature.

After the destruction of the national life of the Jews, nearly their whole energy was directed toward the inner life and found expression in their literature. Their productiveness in this respect was remarkable, and is testified to by the large collections of Hebrew manuscripts and books which are to be found in private and in public libraries. When printing was invented they eagerly seized upon the new art, as it gave them a further means of spreading within their own ranks a knowledge of their literature. The history of Jewish books and Jewish book-making from the technical point of view is one of great interest and has, up to the present time, hardly received systematic treatment.

For the history of their own literature the Jews did little during the Middle Ages, and even when they did work along these lines the motive was in most cases other than purely literary. Such works, for example, as the "Seder Tannaim we-Amoraim," and the well-known "Letters" or "Responsa" by Sherira Gaon on the composition of the Talmudic literature, were not written with the purpose of giving a history of literature, but of proving the validity of tradition.

In modern times Christian scholars were among the first to attempt a comprehensive view of the contents of Jewish literature, though important bio-bibliographical works were compiled by Conforte, Heilprin, and Azulai. Hottinger (died 1667) gave this literature a place in his "Bibliotheca Orientalis," and Otho (1672) sought to describe in the form of an encyclopedia the work and times of the teachers of the Mishnah. The most ambitious work of this kind was the "Bibliotheca Magna Rabbinica" of Bartolocci (died 1687), together with the additions of Imbonati (1694), which was followed up by the colossal work of Johann Christian Wolf (1683-1739). That these attempts failed was due to the fact that the time was not ripe for any such comprehensive presentation, as the preliminary work in detail was still to be done. Order was first wrought in this chaos when the modern spirit of research had engendered what is now known as "the science of Judaism." Zunz's great work, "Die Gottesdienstlichen Vorträge" (1832), was the first attempt to give an accurate account of the development of one branch of this literature, the homiletic. He followed this up with histories of the religious poetry and of the literary productions connected with the Synagogue; and in 1836, a few years after Zunz's first book, a Christian scholar, Franz Delitzsch, in his "Zur Geschichte der Jüdischen Poesie," wrote a history of Jewish poetry which, even at this date, has not been superseded. Steinschneider's remarkable attempt at a comprehensive history of Jewish literature, first published (1850) in Ersch and Gruber's "Allgemeine Encyklopädie der Wissenschaften und Künste," and translated into English (London, 1857) and Hebrew (Warsaw, 1900), has as yet found no imitator, though special departments have received careful treatment at various hands. Neubauer's exhaustive volumes on the history of Jewish literature in France during the fourteenth century have at least placed all the material for that period at our disposal, and Steinschneider's "Hebräische Uebersetzungen des Mittelalters" has brought together a mass of material on the special activity of the Jews in transmitting the science of antiquity to western Europe. In addition to the above publications, attempts have been made at a more comprehensive popular presentation in the compendium of David Cassel (1879), in Karpeles' "Geschichte der Jüdischen Literatur" (1886), and in Winter and Wünsche's "Jüdische Literatur," the last of which is rather a collection of extracts than a history. Making use of all this material, The Jewish Encyclopedia has endeavored to present a faithful picture of what the Jews have done, not only for their own special literature, but also for the great literatures of the world in the various countries in which they have had their abode. Due attention has also been paid to the varied activity of the Jewish press.

Hebrew Philology.

Hebrew philology possesses peculiar interest. The history of the Hebrew alphabet, in its origin and changes, shows the relation of the Jews in the most ancient times to their Semitic neighbors, while its development follows certain lines of cleavage which indicate actual divisions among the Jewish people. Certain peculiarities of grammar and vocabulary, when traced historically to their source, determine whether the Jews developed their language solely on their own national lines or whether they borrowed from other nations, of their own or of different stock. These points are brought out in the Encyclopedia under various general heads. Among the Jews Hebrew philology followed two distinct lines of development. The one was purely from within; for the desire to preserve the text of the Bible intact, for future generations, gave rise to the school of Masoretes, who laid the foundation upon which future scholars built. The other starts from without and is due to the influence of the Arabs, to whom the science of philology was (as Steinschneider has said) what the Talmud was to the Jews. Under this influence and commencing with Saadia, a long line of grammarians and philologists appears, extending not only through Europe but into Africa and even into Persia.

Of course, an encyclopedia like the present can not confine itself to the philological work done by the Jews themselves. The Encyclopedia contains articles upon the chief non-Jewish Hebrew philologists, whether they were influenced by Jewish writers as were Renchlin and his followers, or were not so influenced, as is the case with most of the modern school, Gesenius, Ewald, Stade, and others. This is all the more necessary as during the nineteenth century Jews themselves took but a small part in the philological study of their ancient tongue. The reverse, however, is true of the post-Biblical Hebrew. While in the Middle Ages only one dictionary of the Talmudic language was produced, the "'Aruk" of Nathan ben Jehiel, in recent times and upon the basis of this splendid work, a band of Jewish scholars have made this subject peculiarly their own.

Jewish Bibliography.

A great deal of attention is paid in this work to Jewish bibliography. From Bartolocci to Steinschneider and his pupils, there is a vast amount of unclassified bibliographical material. The Encyclopedia, furnishes, for the first time, the ancient and the modern literature of many thousand topics in alphabetical order; and thus includes, besides complete dictionaries of the Bible, of the Talmud, and of the history and literature of the Jewish people, some approach to a handbook of Hebrew bibliography classified as to subjects, at least. Containing, as it does, however, the contributions of so many collaborators, this work has done its best to introduce some degree of uniformity in the methods of citation employed by the various scholars of different countries.

With regard to proper names, it was found impossible in the present state of Hebrew bibliography to follow a consistent plan; the reader will understand this if he considers the fact that until the eighteenth century the Jews in many countries had no family names. The best-known forms of the names have been selected (to facilitate reference), but in all cases the variant forms have been indicated. It has not been thought wise to follow exclusively either Zedner's system, as shown in his masterly "Catalogue of Hebrew Books in the British Museum," nor that of Steinschneider, in that magnum opus of Hebrew bibliography, the "Bodleian Catalogue"; instead, what seemed to be the best features of the entire bibliographical literature have been combined.

Valuable information may be found concerning the most important Jewish libraries (past and present), as well as the Jewish departments of the public libraries of America and of Europe. Summary histories of the chief Jewish presses are introduced, together with technical details of the typographic art as applied to Hebrew. Among the numerous illustrations which enrich this department of the Encyclopedia are facsimiles of fragments of the oldest and most interesting Hebrew manuscripts in the world.

III. THEOLOGY AND PHILOSOPHY.

The broad subject of theology, including the Jewish religious philosophy of the Middle Ages, has never yet received systematic treatment at the hands of Jews. Thus far very little has been done either in the way of expounding from a philosophical point of view the various subjects pertaining to Jewish belief and doctrine, or of presenting them historically in their successive phases as they developed from their origins in Scripture and tradition, and as they were influenced by other creeds and beliefs. Only a few sporadic attempts have been made in our age to bring the religious ideas and moral teachings of Rabbinical Judaism into anything like systematic form. We may instance Zacharias Frankel, Solomon Munk, Leopold Loew, J. Hamburger, S. Schechter, David Kaufmann, M. Lazarus, and S. Bernfeld as having made valuable contributions in this direction. It was only the practical side of religion—the Law in all its ramifications, the rites and observances—which was systematically codified and summarized by the medieval authorities. The doctrinal side of Judaism, with its theological and ethical problems, was never treated with that clearness and thoroughness or with that many-sidedness and objectivity which historical research in our modern sense of the word demands. Even the great philosophers of the Middle Ages who molded Jewish thought for centuries approached their themes only with the view of proving or supporting their own specific doctrines, and omitted all questions that did not come within the scope of their argument. Consequently, many topics had to be formulated for treatment in The Jewish Encyclopedia, and many of them were suggested by the theological works of non-Jewish writers. Desiring to present both the doctrines and the practises of Judaism in that scientific spirit which seeks nothing but the truth, and this in the light of historical development, The Jewish Encyclopedia, in its theological department, takes full cognizance of the pre-Talmudic sources, the Hellenistic and New Testament literature, and, in addition to the copious Rabbinical literature, treats of the successive stages of Jewish philosophy and Cabala. The various sects (including the Samaritans and Karaites), rationalism and mysticism, conservative and progressive Judaism, are discussed fully and impartially. The mutual relations of Jewish and non-Jewish creeds and philosophical systems and the attitude of Judaism to the social and ethical problems of the day receive due consideration.

Anthropology.

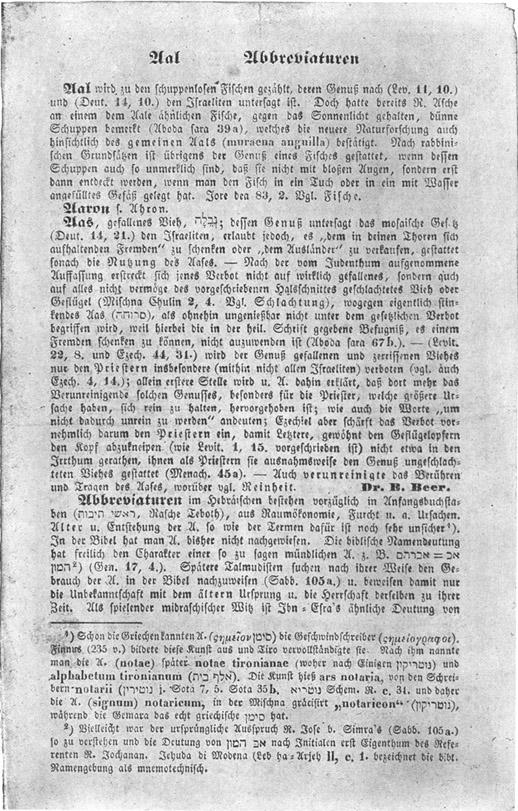

Sample Page of the Steinschneider and Cassel Encyclopedia.

Among the services which The Jewish Encyclopedia has undertaken to render to the general reader is that of enlightening him with regard to characteristic terms (familiar enough perhaps to the Jew) pertaining to Jewish folk-lore and to ancient and modern customs and superstitions, and (what will be a distinctive feature) of acquainting him with the important parts of the Jewish liturgy, its general history and its music. It is hoped that nothing of interest, concerning the character and life of the Jew has been omitted.

There remains a class of topics relating to the Jews, such as their claims to purity of race, their special aptitudes, their liability to disease, etc., which may be included under the general term of anthropology. Very little research has hitherto been devoted to this subject, and it is in this Encyclopedia that, for the first time, the attempt is made to systematize the existing information regarding the anthropometry and vital statistics of the Jews, and to present a view of their social and economic condition.

Illustrations.

It has been one of the special aims of the Encyclopedia to bring together as full a body of illustrative material as possible. Many topics of a historical or archeological character lend themselves to illustration through the reproduction of the remains of antiquity or of ecclesiastical art. Objects connected with the Jewish synagogue service and Jewish modes of worship will be found fully illustrated. Prominent Jewish personages are portrayed, the chief monuments of Jewish architecture are represented by pictures of such synagogues as are remarkable architecturally or historically, and the department of literature is enriched with illustrations of the externals of book-lore. This feature of the work which was placed in charge of Mr. Joseph Jacobs, will, it is believed, prove of great educational value in every Jewish household.

Former Attempts.

In determining the plan and proportions of the present undertaking, the Editorial Board has labored under the special difficulties that attach to pioneer work. No successful attempt has heretofore been made to gather under one alphabetical arrangement all the innumerable topics of interest to Jews as Jews. Apart from the Bible, the only department which has as yet been put, in encyclopedic form is that of Rabbinic Literature, for which there exist encyclopedias, one—the  (Paḥad Yiẓḥaḥ)—compiled by Isaac Lampronti in the seventeenth century in Hebrew, and one prepared in modern times by J. Hamburger, the "Realencyklopädie für Bibel und Talmud," in German. Each of these productions labors under the disadvantage of being the work of one man. Of the more comprehensive encyclopedia planned by Rapoport,

(Paḥad Yiẓḥaḥ)—compiled by Isaac Lampronti in the seventeenth century in Hebrew, and one prepared in modern times by J. Hamburger, the "Realencyklopädie für Bibel und Talmud," in German. Each of these productions labors under the disadvantage of being the work of one man. Of the more comprehensive encyclopedia planned by Rapoport,  ('Erek Millin), only the first letter appeared in 1852. The plan of a publication somewhat on the same lines as the present was drawn up by Steinschneider in conjunction with Cassel as far back as 1844, in the "Liveraturblatt des Orients," but the project did not proceed beyond the prospectus (a specimen page from which is shown on the opposite page) and a preliminary list of subjects. Dr. L. Philippson in 1869 and Professor Graetz in 1887 also threw out suggestions for a Jewish encyclopedia, but nothing came of them.

('Erek Millin), only the first letter appeared in 1852. The plan of a publication somewhat on the same lines as the present was drawn up by Steinschneider in conjunction with Cassel as far back as 1844, in the "Liveraturblatt des Orients," but the project did not proceed beyond the prospectus (a specimen page from which is shown on the opposite page) and a preliminary list of subjects. Dr. L. Philippson in 1869 and Professor Graetz in 1887 also threw out suggestions for a Jewish encyclopedia, but nothing came of them.

The Present Work.

The present undertaking is the realization of an ideal to which Dr. Isidore Singer has devoted his energies for the last ten years. After several years spent in enlisting the interest of European scholars in the enterprise, he found that it was only in America that he could obtain both that material aid and practical scholarly cooperation necessary to carry out the scheme on the large scale which he had planned. Thanks to the enterprise and liberality of the Funk & Wagnalls Company, which generously seconded the energetic initiative of Dr. Singer, the cooperation of the undersigned staff of editors, together with that of the consulting boards, both American and foreign, was rendered possible. The preliminary work was done in the winter of 1898-99, by Dr. Singer, Professor Gottheil, and Dr. Kohler. These were soon joined by Dr. Cyrus Adler, of Washington, D. C. ; Dr. G. Deutsch, of Cincinnati; Dr. Marcus Jastrow and Prof. Morris Jastrow, Jr., of Philadelphia; and Prof. George F. Moore, of Andover. Organization of the work was effected by these gentlemen at meetings held in New York, March 1 and 6, and July 12, 1899, Dr. I. K. Funk, of the Funk & Wagnalls Company, presiding, and the plan of operation submitted by the firm was adopted by them. To these was added later Mr. Joseph Jacobs, of London, as well as Dr. Louis Ginzberg and Dr. F. de Sola Mendes, both of New York city. Professor Moore, having assumed additional duties as president of the Andover Theological Seminary, found himself obliged to withdraw, and Prof. C. H. Toy was elected in his place in January, 1900.

Transliteration.

The carrying out of the project on so large a scale presented peculiar difficulties. To reduce the work of nearly 400 contributors, writing in various tongues, to anything like uniformity was itself a task of great magnitude, and necessitated the establishment of a complete bureau of translation and revision. The selection of the topics suitable for insertion in such an encyclopedia involved labor extending over twelve months, and resulted in a trial index of over 25,000 captions. The determination of the appropriate space to which each of these subjects was entitled was no easy task in the absence of any previous attempt in the same direction. The problem of the transliteration of Hebrew and Arabic words has been very perplexing for the members of the Editorial Board. While they would have preferred to adhere strictly to the somewhat elaborate method current among most Semitic scholars, the repellent effect of strange characters, accentual marks, and superscript letters deterred them from using it in a work intended as much for the general public as for scholarly use. There were also typographic difficulties in the way of using the more elaborate scheme. The board trusts that the system pursued here, which is, in the main, that proposed by the Geneva Congress of Orientalists, and adopted by the Royal Asiatic Society of England, the Société Asiatique of Paris, and the American Oriental Society, will suffice to recall to the Jewish scholar the original Hebrew, while indicating to the layman as close an approximation to the proper pronunciation as possible. Even here, however, having to deal with contributions emanating from scholars using different schemes of transliteration, they can not hope to have succeeded altogether in avoiding lack of uniformity. It may perhaps be well to emphasize the fact that names occurring in the Bible have been throughout kept in the form familiar from the King James Version of 1611.

While acknowledging the possibility—nay, the certainty—of errors and omissions in a work so comprehensive and so full of minute details as the present work is, the editors consider themselves justified in asserting that no pains have been spared to secure accuracy and thoroughness. Each article has been subjected to a most elaborate system of revision and verification, extending in each case to no less than twelve different processes. Prof. Wilhelm Bacher, of the Budapest Seminary; Rev. Dr. F. De Sola Mendes, Mr. Louis Heilprin, and other scholars, in addition to the departmental editors, have read through all the proof-sheets with this special end in view.

Acknowledgments.

It remains only to give due acknowledgment to the many institutions and friends, other than contributors, who have rendered services to the Encyclopedia. The Hon. Mayer Sulzberger, of Philadelphia, has loaned many valuable and rare works for the purposes of verification and illustration. Much is due to the New York Public Library, particularly to its director, Dr. J. S. Billings, to Mr. Charles Bjerregaard, chief of the Readers' department, and to Mr. A. S. Freidus, chief of the Jewish department, for special privileges accorded and assistance rendered; to the United States National Museum, Smithsonian Institution, which has placed at the disposal of the Encyclopedia photographs of many objects of Jewish worship preserved in the department of Oriental Antiquities; to the Columbia University Library; to the American Jewish press for repeated notices; and to the proprietors of the "Jewish Chronicle" (London), for having placed the files of their journal at the disposal of the Encyclopedia. M. Vigouroux's "Dictionnaire de la Bible," now in process of publication, has been of especial value in suggesting the latest sources of Biblical illustration. Pictorial material has been loaned by, among others, Mr. J. D. Eisenstein, Mr. Frank Haes, Mr. Arnold Brunner, Prof. R. Gottheil, and the Palestine Exploration Fund, for which the editors and publishers beg to return their acknowledgments.

The Editorial Board desires especially to thank the Rev. Dr. I. K. Funk for the unfailing tact and matchless generosity with which he has met all their wishes and smoothed away many difficulties. Pioneer work as this has been, the need of encouragement to perseverance under adverse conditions was repeatedly felt by all concerned, and this encouragement has been continuously extended to us by our respected chief. Our thanks for courteous consideration are also eminently due to Mr. A. W. Wagnalls, vice-president of the Funk & Wagnalls Company; to Mr. R. J. Cuddihy, its treasurer and general manager, for his organizing skill; to Mr. Edward J. Wheeler, literary editor of the Company and member of the American Board of Consulting Editors of this work; and to Mr. William Neisel, chief of the manufacturing department, and his assistant, Mr. Archibald Reid. Mr. Herman Rosenthal, to whom the important section of the history and literature of the Jews in Russia has been entrusted, has faithfully discharged his difficult task.

We are indebted for much valuable cooperation and watchful care to the restless energy of Frank H. Vizetelly, the Secretary of the Editorial Board, to whom was entrusted the general office supervision of this work in all its stages, and whose executive ability, practical knowledge, and experience have been most useful. Mr. Isaac Broydé, by his thorough knowledge of Arabic, has been of the greatest service to the work; while Mr. Isaac Broydé, by his thorough knowledge of Arabic, has been of the greatest service to the work; while Mr. Albert Porter, formerly of "The Forum," as chief of the subeditorial staff of the Encyclopedia, has rendered intelligent and attentive service in the preparation of the copy for the press. Mr. Moses Bher, who has been connected with the work almost from the beginning, has been of great assistance to the office-staff in various departments, and especially in verifying the Hebrew. Hearty thanks are due also to all the members of the office-staff—translators, revisers, proof-readers, and others—for their faithful, painstaking service in their respective departments.

The editors have felt a special sense of responsibility with regard to this work, in which for the first time the claims to recognition of a whole race and its ancient religion are put forth in a form approaching completeness. They have had to consider susceptibilities among Jews and others, and have been especially solicitous that nothing should be set down which could hurt the feelings of the most sensitive. They consider it especially appropriate that a work of this kind should appear in America, where each man's creed is judged by his deeds, without reference to any preconceived opinion. It seemed to them peculiarly appropriate under these circumstances that The Jewish Encyclopedia should appear under the auspices of a publishing house none of whose members is connected with the history or tenets of the people it is designed to portray. Placing before the reading public of the world the history of the Jew in its fullest scope, with an exhaustiveness which has never been attempted before—without concealing facts or resorting to apology—The Jewish Encyclopedia hopes to contribute no unimportant share to a just estimate of the Jew.

- Cyrus Adler

- Gotthard Deutsch

- Louis Ginzberg

- Richard Gottheil

- Joseph Jacobs

- Marcus Jastrow

- Morris Jastrow, Jr.

- Kaufmann Kohler

- Frederick de Sola Mendes

- Crawford H. Toy

- Isidore Singer.